Britain’s seventeenth century history has lumbered into the news this week, with the High Court of Justice’s judgment that, according to the law of this country, the government cannot trigger the EU-exiting Article 50 without direct parliamentary approval. Two of the key precedents cited by the judges are the writings of Sir Edward Coke, an influential early-seventeenth-century constitutional lawyer, and the Bill of Rights, which was produced after the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688-9. Both state that parliament is the sovereign maker of law in Britain, and are therefore the only ones who can change the law. These documents were originally produced in very specific contexts, and certainly not everyone at that time would have agreed with them (least of all ‘divine-right-of-kings’ Charles I, who literally lost his head over this matter), but their enduring legacy evidently cannot be denied.

Sir Edward Coke: enemy of the people?

Or can it? A section of the national press have not exactly taken this judgment well. Their outcry, casting the High Court judges as ‘enemies of the people’ (among other things), has in turn raised hackles, as well as provoking fears that there could be more serious consequences to such rhetoric. On the other hand, it is interesting to take a historical perspective on this too, as the newspaper industry in Britain has its origins in the civil wars of the 1640s.1 The paranoia, partisan hyperbole, and vicious personal attacks we have witnessed recently would certainly be familiar to anybody who flipped through the pages of Mercurius Aulicus or any of its fellows during the civil war years.

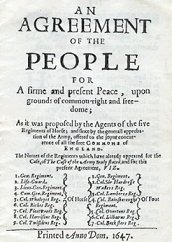

The headlines also made me think about The agreement of the people, a manifesto from the end of the civil wars written by the radical group the Levellers, which I covered in a seminar last week.2 One of The agreement‘s proposals (in article IV) was ‘That the power of this and all future representatives of this nation is inferior only to theirs who choose them’ – or to put it another way, parliament should be sovereign, but the eponymous ‘people’ should be sovereigner. No doubt the outraged newspaper editors and their equally outraged readers will feel that the Levellers were on to something here.

The Levellers’ agreement.

Except that this is where it all gets tricky, because The agreement was rather vague as to who ‘the people’ were. Did it include the defeated royalists whom parliamentarian Levellers probably didn’t trust? Or Catholics, Jews, or Muslims, whose faiths were illegal in England? Should there be a minimum property qualification for voters, as had previously been the case? How about women? The agreement‘s significant phrase ‘native rights’, which we discussed in some detail in the class, also suggests that these were considered to be exclusively English privileges (and this very same decade saw leading parliamentarians begin to participate enthusiastically in the transatlantic slave trade, suggesting they weren’t particularly exercised by universal human rights).3 Similarly the French revolution, which we also looked at last week, produced the Declaration of the rights of man, but nevertheless the revolutionary government effectively denied those same rights to thousands of people during the Terror. Personhood is often, rather shamefully, in the eye of the beholder.

To apply these reflections to the present, if the judges are the enemies, then who exactly are the people on whose behalf the newspapers claim to speak? Certainly not the scared, vulnerable evacuee children from Calais these same newspapers have so enthusiastically targetted and depersonalised as threatening ‘immigrants’. Presumably not the 48% of voters who did not support Brexit – or the many who did not and could not vote. Perhaps not even those who voted for Brexit but would like to see it debated in parliament.

Indeed, this media apoplexy is merely the latest of many efforts since the referendum to suppress a variety of opinions, and to turn a difference of just 2% into the overwhelming and unambiguous roar of a patriotic vox populi. Whatever position we take on the Brexit debate itself, we should be deeply suspicious of such crude and bullish attempts to control the meaning of events. Senior members of the government have been engaged in these attempts just as much as the media, and so far have failed to comment on yesterday’s headlines.4 Yet the High Court’s decision in favour of parliamentary sovereignty might inject some more balance, scrutiny, and compromise into proceedings. Historically speaking, that is what parliamentary sovereignty is supposed to do.

Next week, I am teaching classes on colonial empires in North America, and on the American and Haitian revolutions. I wonder if there are any upcoming major political events that might relate to those particular topics…

[1] See Joad Raymond, The invention of the newspaper: English newsbooks, 1641-1649 (Oxford, 1996).

[2] On The agreement see Rachel Foxley, ‘From native rights to natural equality: the agreement of the people (1647)’, in Rachel Hammersley, ed., Revolutionary moments: reading revolutionary texts (London, 2015), pp. 11-18, which also provides recommendations for further reading.

[3] I made similar points about Magna Carta in my last post. For the slave trade and the civil war, see my article on trade to West Africa, and the sources cited there.

[4] Since I wrote this post, the Ministry of Justice have issued a statement by the Lord Chancellor. It reiterates only the most basic of legal principles, and says nothing about the headlines, so I do not see any need to change the original wording.

Engagingly written and very interesting. I always appreciate historical light like this being shed on modern matters.